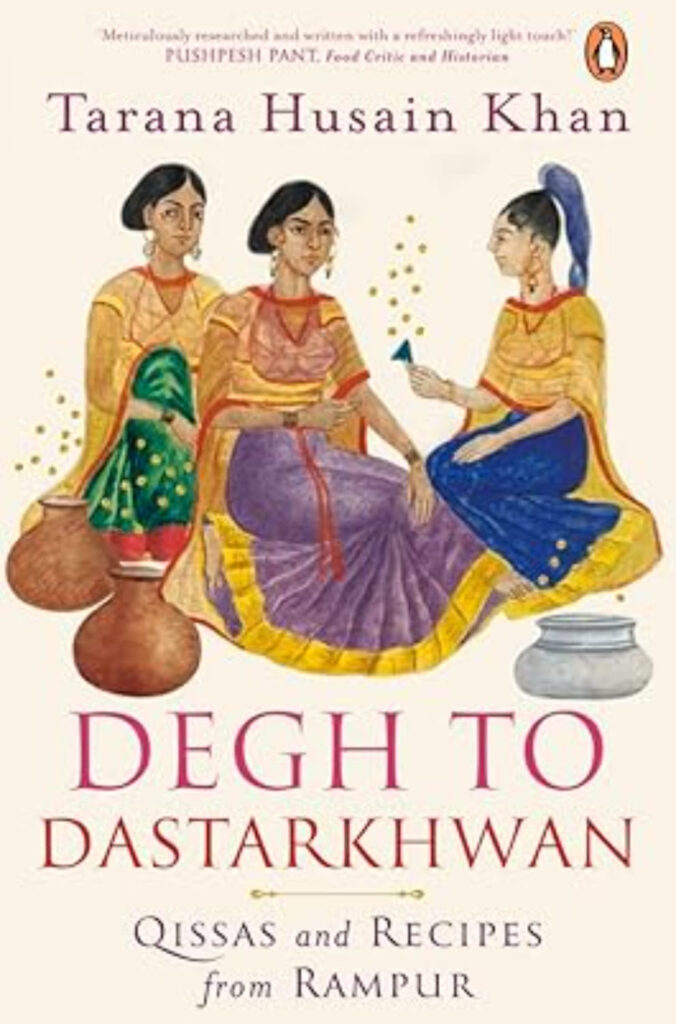

Degh to Dastarkhwan: Qissas and Recipes from Rampur

From food researcher and writer Tarana Husain Khan, Degh to Dastarkhwan is a collection of essays which links history and memories around the theme of food. Tarana was an indifferent eater and an unenthusiastic cook until a chance encounter with a nineteenth-century Persian cookbook in Rampur’s fabled Raza Library started her off on a journey into the history of Rampur cuisine and the stories around it.

How can you explain the texture, taste and smell of something that has ceased to be? A sweet named ‘dar e bahisht’, which translates to ‘gateway to heaven’, was probably created in Rampur to be distributed on ‘chellum’ festival and prepared by special cooks till the seventies. Till a generation back Rampuri cuisine had a repertoire of dishes which could rival the fabled dastarkhwans of Mughal emperors. Most of these dishes have become intergenerational food memories- talked about but never experienced. Thus foods like dar e bahisht, kundan qaliya, hababi, the vast repertoire of biryanis, qormas and kababs, among others, became the subject of food nostalgia.

Part food memoir, part celebration of a cuisine, abbreviated and almost forgotten, the book answers the question- what constitutes and distinguishes the Rampuri cuisine? Each chapter takes the readers through different terrains, from the warm sweetness of childhood memories to the glamorous narrative of court life and the gritty reality of the humble street shops. Using food as an anchor, this book weaves through culinary memories and oral history of Rampur to reveal a vibrant culture with a grand past.The narrative also lends itself to a gendered retelling of Rampur by foregrounding the invisible women, the practitioners and keepers of food and culture and shares recipes from Rampur homes.

The book is peopled with compelling characters from all walks of life who narrate their stories. In an interview, Mahpara Begum, the nearly hundred-year-old dancer at the court of Nawab Raza Ali Khan, speaks of feasting on the leftovers from the Nawab’s table and the glamorous nightlife at the court. In a chapter on the sublime ‘gulathhi’ sweet, Munna Khansama shares the oral history of the creation of the unique dish. The spiritual ambience and langar at the Sufi shrine of Shah Baghdadi, bring to mind the qawwali mehfils at the author’s great grandfather’s grave. Thus connecting food memories, and oral history around the food culture of Rampur, each chapter ends with an authentic recipe from Rampuri homes, old khansamas and ancient cookbooks.

The memories and cultural practices around food form the core of the book. Each chapter unveils some aspect of cultural ethos, some quirky food traditions and the reader feels drawn into the intimacy of ‘Rampuriyat’ and the warmth of its cuisine. Food becomes a lens for viewing the city and its people, a metaphor for emotions lived and remembered.

Praise for Degh to Dastarkhwan

“Meticulously researched and written with a refreshingly light touch. A gem!”

––Pushpesh Pant, Food Critic and Historian

‘Peppered with food memories, anecdotes and unique recipes from Rampur and its largely forgotten, grand cuisine, this is the kind of culinary documentation that leaves you salivating on so many levels.’

––Thomas Zacharias, Chef and Founder of The Locavore

‘Beautifully captured the essence and contribution of Rampuri Cuisine. Rampur has a legacy of a very bold style of food by some legendary khansamas of the time. Tarana ji has brought to light the stories, recipes and the thought behind the cuisine of a bygone era.’

—Kunal Kapur, Chef and Restaurateur

“Tarana Husain Khan’s absorbing new book, Degh to Dastarkhwan: Qissas and Recipes from Rampur, is more than just a cookbook or a memoir. The collection of essays braids history and memories, stories of compelling people, migration, with food as the fulcrum driving the narratives.”

-The Hindu

REVIEWS

Tarana Husain Khan’s ‘Degh to Dastarkhwan’ brings fables, flavours of Rampur

Tracing Rampur’s History from Degh to Dastarkhwan | Tarana Husain Khan

That the faculty of taste is fundamental to meaning making practices is now a commonplace idea. For instance, some food items make us salivate in desire, the consumption of which brings pleasure.

Writer and cultural historian Tarana Hussain Khan captures the lost culinary traditions of Rampur in her food memoir